"Attila"(s) Update and "VZ: Volodymyr Zelenskyy and the Making of a Nation" by Dmitry Bykov

Couple notes on recent releases and forthcoming titles

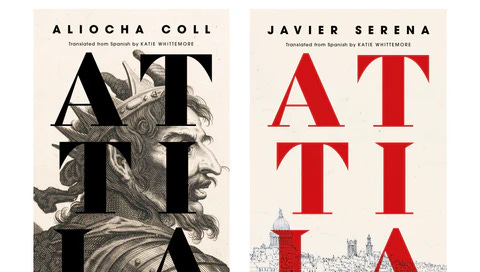

On April 1st, we finally released a plan six years in the making, with both Attila by Aliocha Coll and Attila by Javier Serena coming out on the same day.

Publishing what is likely the most experimental novel in translation to come out in 2025—far more difficult to wrap your head around than any other titles in this category—and a book about the author of that book was considered by many to be a rather big, risky swing. (Looking at you, Consortium Book Sales & Distribution.) There are so many opportunities for confusion given the matching titles and similar covers, but we believed in our readers, assuming they’re sophisticated enough to make sense of this literary event.

And so far, this has paid off in spades. Coll’s Attila has sold more than 3 times the pre-release projections (which is like 8.0 Books Above Replacement for all the statheads out there), and the surge in interest in both Serena’s Attila and his earlier, Bolaño-centric novel, Last Words on Earth has been astonishing.

The phenomenal response from readers, critics, and podcasters has been driving these sales, and we’d like to take a moment to just appreciate some of the highlights—and hopefully whet your interest in these books!

First up is Daniel Yadin’s article in Publishers Weekly, “Why a Homophonous Pair of Spanish Novels Were ‘Catnip’ to Open Letter”:

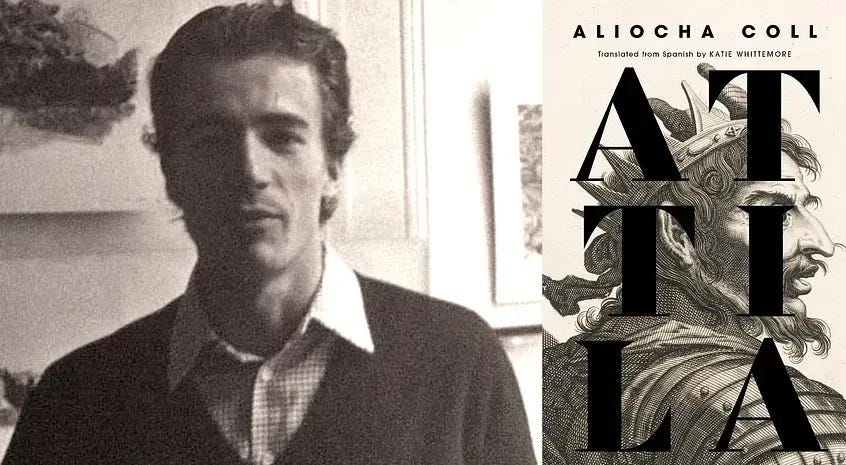

[Katie] Whittemore, who lives in Valencia, Spain, had been tipped off to Coll by Javier Serena, a young Spanish novelist who hoped Whittemore would translate his most recent books—a pair of novels each dramatizing the lives of two writers devoted to their craft—into English. The first centered on Roberto Bolaño, a titan of Chilean literature who “could not have become more successful,” Whittemore says. But the other fictionalized Coll, who was scarcely read even in his native Spain and died in squalor by his own hand shortly after completing Attila, his magnum opus, in 1990. Serena’s 2014 novel, also called Attila, imagines the last months of Coll’s life amid his mad drive to complete his manuscript.

At the bar, the pair googled the enigmatic Coll, learning that Spanish writer Javier Marías eulogized him as a writer with “a verbal talent and sense of rhythm of the first order.” Mega-agent Carmen Balcells—who shepherded many Spanish-language writers to international fame—considered Coll the one author she could never get off the ground, with work too strange, difficult, and dark for a wide audience. This thrilled both Whittemore and Post, a prominent publisher of literature in translation. “This,” he recalls thinking, “is catnip.”

Now if you’re interested in more of Katie Whittemore’s perspective on this project and what it was like to translate it, you should turn to her introduction (which we’ll run later this week), but short of that, you can listen to her on the always impressive Beyond the Zero podcast:

In terms of approaching the books themselves—in particular, Aliocha Coll’s Attila—there are two great Substack posts that I’d like to call your attention to. The first by Blake Butler (author, most recently, of Molly):

Attila is the kind of book that writes itself. I mean this in an opposite way than it might seem: that it exists solely because its author did, and because that person—Aliosha Coll, which is a pseudonym—took the time to exchange himself for the right to transfer it from nonessence into obscurity.

Everything is its opposite opposite. Without exactly the traits and experience any exclusively figuratively sane author has been granted in order to sit in the same room for years and lose himself between the words, we might as well have had just another butcher standing behind a glass case full of loose meat waiting to get paid in exchange for blood money. [. . .]

Attila is perhaps the most coherent book written in the last 50 years. It is not, however, a Finnegans Wake, despite the author’s assertion of that tome as “the 'starting point’ for literature” as his bio at the back of its original translation into English verily points out. Nor is it an animal shriek, or a finger trap, or sandpaper, as all of those would be like butter on a wound; comparatively, to break the metaphor entirely, Attila is skin.

In addition to Butler’s inventive, captivating meditation on Attila, Clara posted a very in-depth close reading of the novel:

The surface of Attila is perturbed with History and Empire. Its elemental core swirls with the forces of Nature.

When the setting is a tottering Rome, it’s mostly safe to assume the book will concern itself with the reasons civilizations fall, what can be done to prevent this, what can't be done, and why such questions are wrongly posed. What could last longer than its own duration? Attila has all of this, in abundance.

But Aliocha Coll did not devote the last of his life and his sanity to a merely political theme. The collapse of civilization is only one facet of a deeper, more all-encompassing dilemma. There’s a Gilgameshian drive at work, a longing for Eden and immortality that reaches beyond the personal and the collective to address the very structure of reality.

. . . like an egg, which, having reached a state of perfection, should want to make itself perfectible, never new again . . .

The dilemma manifests itself in language. If the writer seems to battle against language, to want to tear it apart and dislocate it, this is less a literary experiment than a treatment of language itself as the symptom of a disease.

Before we move on to a little bit about Bykov’s VZ, and since this has been discussed in my DMs and on that Beyond the Zero podcast, I wanted to lay out four ways to approach reading this project, with at least one pro for each option:

Read Serena’s Attila first, then Coll’s: This is helpful for providing a context for what you’re about to experience so that Coll’s work isn’t so offputting.

Read Coll’s Attila first, then Serena’s: This prevents Serena’s depiction of Coll to taint your reading. Will emphasize Coll’s expansive view of literature itself in contrast to focusing on Serena’s look at his imagined personal life.

Read part of Coll, then part/all of Serena, then back to Coll: This is my preferred method. You get to taste Coll free of bias, and then, when you’re totally lost, turn to Serena for some insight and grounding.

Read part of Serena, then part/all of Coll, then back to Serena: This provides a frame for who Coll is (the first part of Serena’s Attila is a perfect introduction), then lets you work through Coll’s masterpiece before finding out what happened to him (or at least to his stand-in) during the completion of this book.

So many avenues to explore! And no matter what you choose, I’m certain you’ll be enthralled by these literary gems.

We’ll have a lot more about Dmitry Bykov & John Freedman’s VZ: Volodymyr Zelenskyy and the Making of a Nation over the next few weeks building to its official June 10th release, but since copies are available now, I wanted to draw some attention to this incredibly relevant book.

What you’ll find below is the letter going out to all of our subscribers, which, hopefully, provides enough context to pique your interest:

Although we've done a number of nonfiction works over the course of our history—from Dubrakva Ugresic's personal essays to our Polish Reportage series—we've never done a book that's quite as timely or politically relevant as VZ.

This book came to us via a conversation with Prof. John Givens at the University of Rochester, who helped bring famous writer and dissident, Dmitry Bykov, to the U of R as the inaugural "Humanities Center Scholar in Exile" visiting professor. Bykov is a prolific writer with at least ninety books, including five biographies, twelve novels, and twenty poetry collections.

His "Citizen Poet" project on YouTube, along with participation in various antiauthoritarian protests landed him in hot water, and after refusing on two occassions to meet with Putin, he was poisoned by the same FSB operatives who then poisoned Alexei Navalny. He was banned from teaching in Russia or appearing on Russian state-controlled media. He was declared a "foreign agent" by the Russian government when he left the country in 2022, and his works are now officially banned in Russia.

VZ: Volodymyr Zelenskyy and the Making of a Nation is, in many respects, a biography of Zelenskyy, but one that is measured and quite comprehensive, looking at the conditions that led to Zelenskyy's election, his early struggles, and his transformation through Russia's invasion of Ukraine. It's as up-to-the-minute as can be for a published and bound book, with the final chapter written just a couple months ago.

Nevertheless, this conflict rages on and has taken some unnerving turns as of late, thanks in large part to Trump and his administration, who are happy to play their traditional role as bullies who gladly sidle up to Putin, and who are spreading false narratives about the invasion and ensuing war. Through extensive research and dozens of conversations with high ranking officials, VZ does its best to articulate the ins and outs of the situation in Ukraine, and serves as a powerful counterpoint to Trump's garbage.

Stay tuned for Whittemore’s spectacular introduction to Coll’s Attila, and for more information about VZ and all of the books we have coming out this fall and winter, including a new book by Andrés Neuman, the winner of this year’s Contemporary Bulgarian Writer Award, Lara Moreno’s follow-up to Wolfskin, the first book to win the Armory Square Prize for South Asian Literature in Translation, and a new reprint of a classic Juan José Saer novel.

That's amazing to hear! I passed it along to Katie Whittemore, who is, I'll bet, going to be very interested in hearing that this is influencing your dreams . . .

I’m finishing Coll’s Attila now, and will then move on to Serena. It’s been one of the most rewarding experiences of my life, and not just in the ordinary sense of, say, the experience of reading it. There have been accompanying visions while falling asleep in the sun after reading it, dreams, and imagined permutations of word groupings in the text of the book that have made Attila more of an event than a simple reading experience. It’s quite magical. Thanks so much for taking a chance on it. I’m happy to hear that it’s paying off.