Every Translation Database Post Hides a Listicle

The history of the Translation Database through four dates and four books.

TL;DR: Since mentioning it in last month’s newsletter, I’ve added almost 200 titles to the Translation Database, bringing the grand total to 10,072 entries. (Feel free to download that and play with the data however you’d like. And hit me up if you’d like a FileMaker version.) There are still a ton of titles to be added, but every month I’ll be posting some sort of update utilizing the database to explore a corner of the literary translation world.

If you’d like to help fill out this database—the only one of its kind, which isolates all works in translation published in the U.S. for the first time—you can either fill out this form, email me information about your book, or send a review copy to our office. (As time goes on, I’ll be writing and podcasting more and more about new translations, so if it’s possible, a hard copy is much appreciated.) Same thing if you find an error in the data. I’ve been typing these all in by hand for almost 20 years, so there’re bound to be slip ups.

For more information about the history and state of the Translation Database—and some book recommendations—keep on reading.

2023

It’s been over two years since I really updated and wrote about the Translation Database. “The Visual Success of Women in Translation Month” was posted in early-August 2023 to demonstrate that, for the first time since the Translation Database came into existence, there were a virtually identical number of works of fiction written by women being translated into English as works written by men.

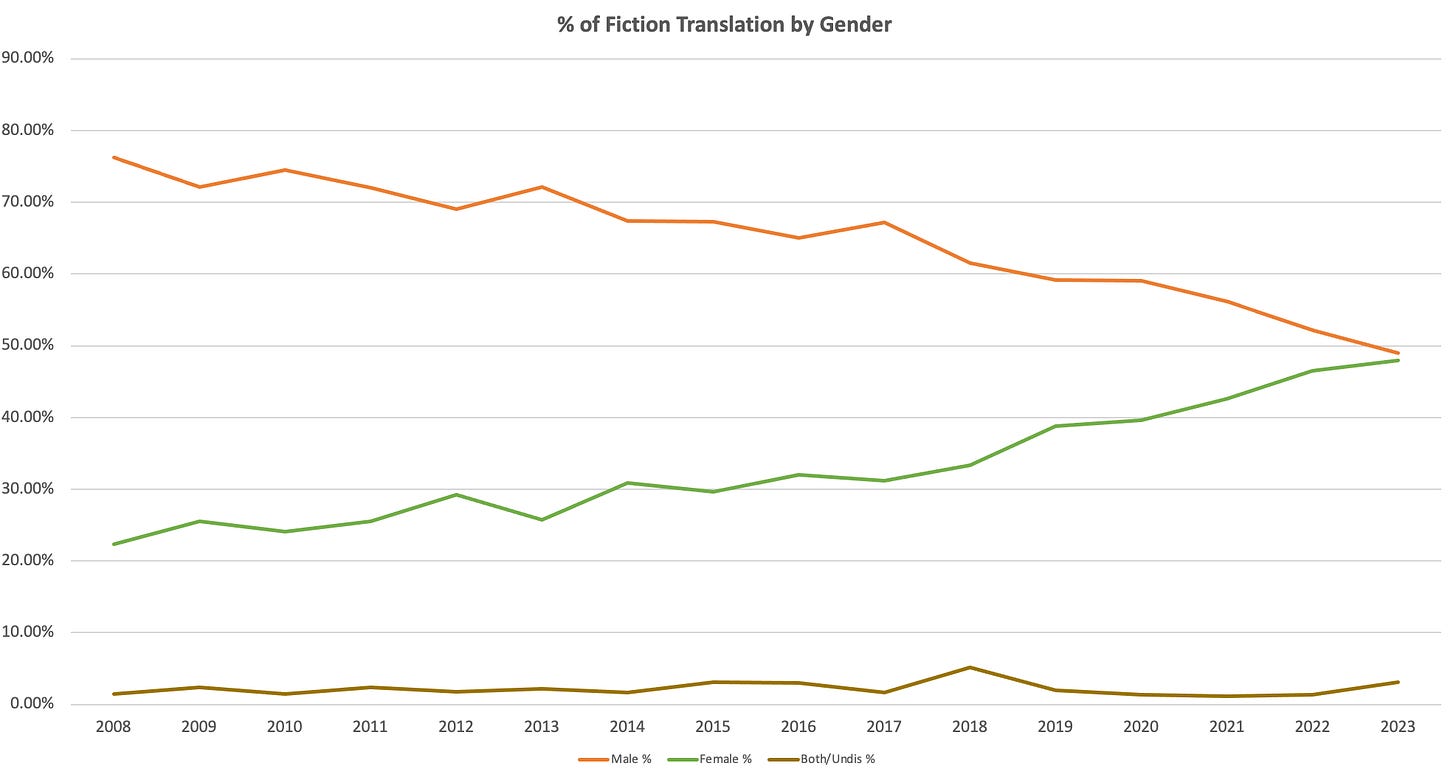

Here’s the chart that drove this post:

My “analysis” of this trend—such as it was—focused on the success Women in Translation Month (Meytal Radzinski’s brainchild, founded in 2014) had in correcting this imbalance. To go from a period in 2008 where the average translation was 4 times more likely to have been written by a man than a woman to being almost exactly equal in 2023 is a hell of a shift.

And this sort of analysis is more or less why this database was founded. If you’ve listened to a single one of my podcasts, or read Three Percent circa 2018–2021, you know how much of a data and stats dork I am. I love downloading FanGraphs leader boards, I love looking up how many books have been translated from Hungarian over the past five years. The Translation Database scratches a sort of itch, while also helping me feel connected to what works of international literature are coming out, and from who.

Besides, data makes for the best posts. Just as every fun fact hides a lie, every post I write hides a listicle—and there’s nothing better than a big data set to generate a list.

For example, in plotting how to wed big(gish) data with a focus on individual books for this post, I decided to use the Translation Database to find one title to highlight each meaningful year in the database’s development.

So, to start, there are currently 29 titles included the Translation Database that came out in August 2023. Fourteen of these are fiction. And nine of those were written by women, including:

The Princess of Darkness by Rachilde, translated from the French by Brian Stableford (Snuggly)

I’ve never heard of Rachilde, and don’t really read a lot of horror, but the opening of the description on iPage caught my attention:

Rachilde, the writer whose formal name was Marguerite Vallette-Eymery (1860–1853), is primarily remembered today for her sensational decadent novel Monsieur Vénus (1884), which was prosecuted as pornography in Belgium, where it was initially published, resulting in a conviction and a sentence of two years’ imprisonment imposed in absentia.

Snuggly (41 titles in the database) has always done interesting books, as has Wakefield, which brought out The Tower of Love in 2024—one of three titles by Rachilde that came out last year.

I’m willing to go wherever Wakefield Press takes me, so I’m totally in on this creepy sounding book:

When Jean Maleux, a young sailor, is appointed assistant keeper of the Ar-Men lighthouse off the coast of Brittany, he is drawn into a dark world of physical peril, sexual obsession and necrophilia. The lighthouse is home to the eccentric, embittered keeper Mathurin Barnabas: an irascible and grizzled old man who appears to be more animal than human.

Time passes in alternating stages of mind-numbing monotony and bouts of horror as our hero struggles against the endless assaults of wind and loneliness, with only his duties and his mute companion for distraction. The sea evolves into a wild force and the lighthouse itself into a monster that Jean must tame if he is to survive.

2025

Putting aside the happy accident of finding an interesting sounding author via the Translation Database—one I doubt I would’ve come across in any other way, like at the bookstore, in the library, on Instagram—what jumps out at me from that bit of research is that there are only 29 titles in the database from August 2023. There are currently 44 titles listed as having come out in August 2022 and 66 in August 2018, but only 30 in August 2021. Which raises the question: how complete is the Translation Database?

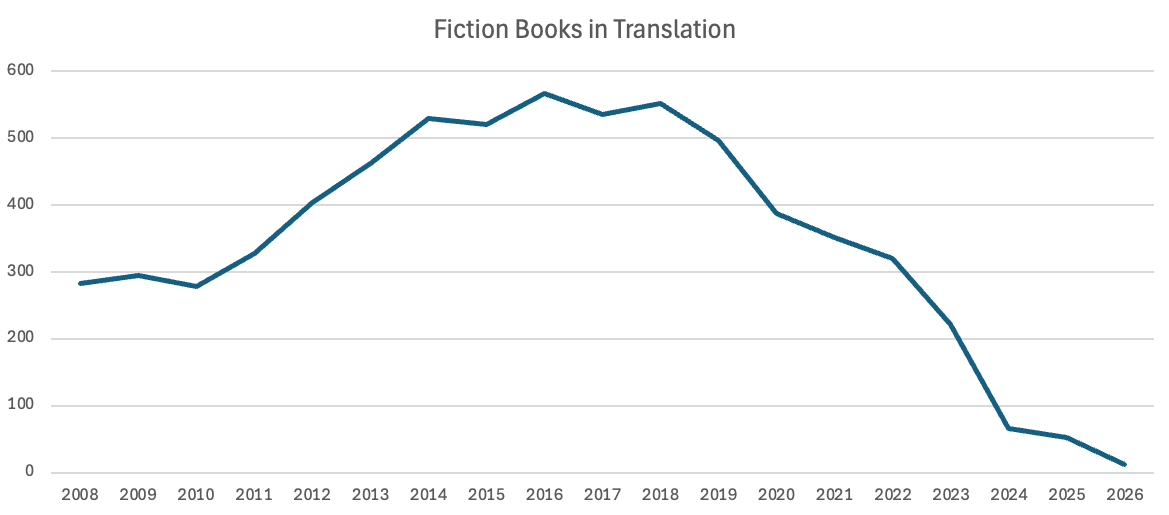

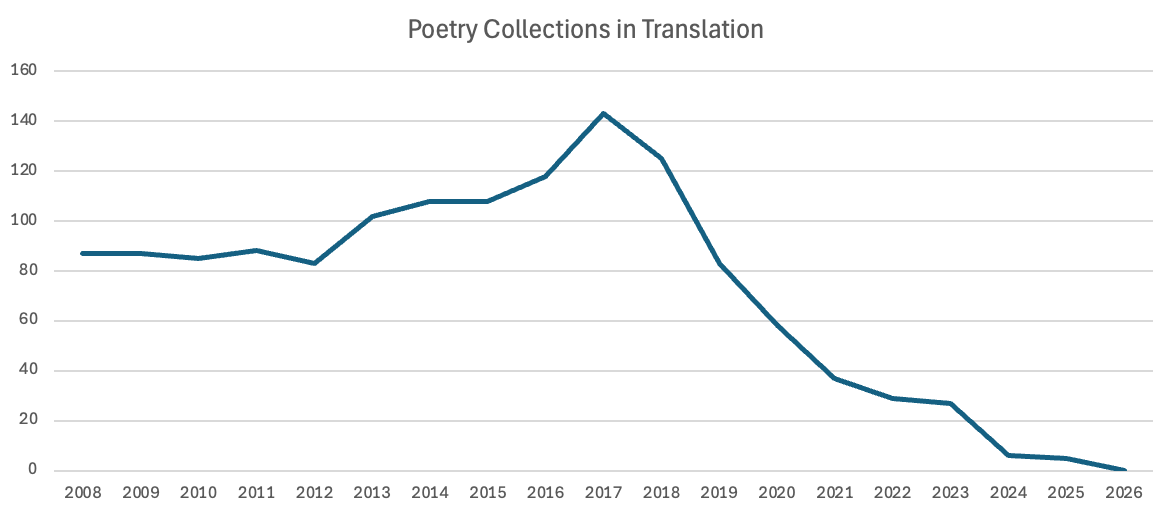

Well, in short, it gets a bit sketchy after 2020. That was when data got wonky, life stayed weird, and the entries into the database started to tail off. The database is always a work in progress though, and the only thing keeping it from being more accurate is time.

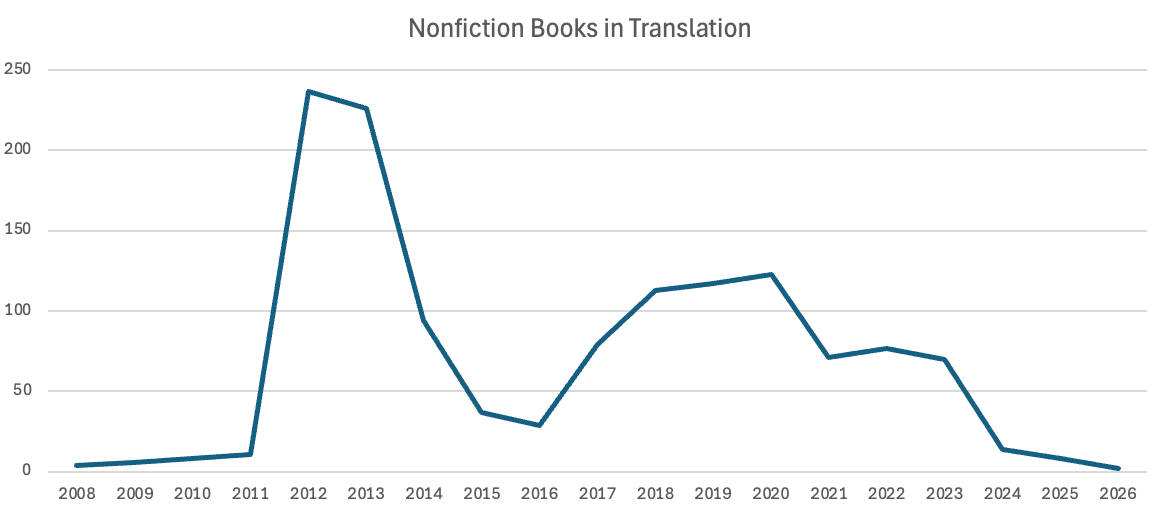

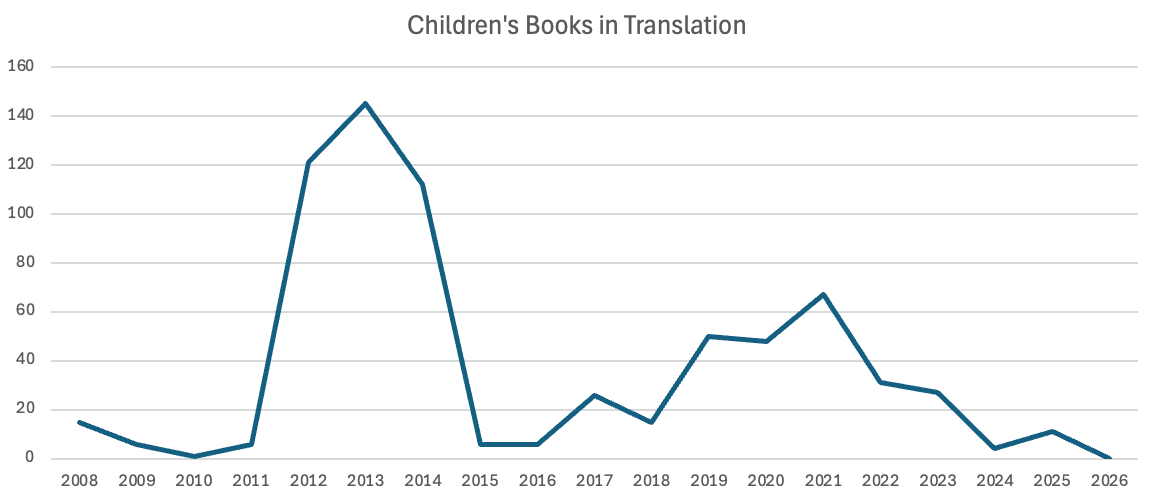

But as I start to rehab this and make it a valuable listicle-generating machine again, I wanted to get a snapshot of where things are now. So I ran a few charts to see which years I should focus on first. The data is . . . pretty telling.

I do believe that things tailed off a bit in 2020–2022 compared to 2018–2019, but that precipitous drop is more a symbol of my data entry laziness, not necessarily the publishing industry.

But the Nonfiction and Children’s book charts are the ones I want to spend a bit more time explaining.

When I initially started tracking translations, I only focused on fiction and poetry, since we all need boundaries. But around 2014, the Italian government asked me to put together a report on the state of Italian literature in translation, and to get a fuller picture of what was going on, I started gathering data about nonfiction and children’s titles, going back a few years to provide a bit more context.

And then, when the database relocated to Publishers Weekly1 we made this data public and I started trying to keep it up across all four categories. That said, it’s very clear from the charts above that everything pre-2011 still needs to be captured, and that 2015 onwards is suspect.

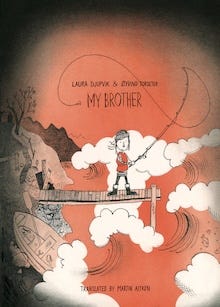

At the moment, the 2025 information is embarrassingly incomplete, but there is info on eleven children’s books, including:

My Brother by Laura Djupvik, translated from the Norwegian by Martin Aitken (Elsewhere Editions)

To be honest, identifying the children’s books is kind of a drag. Not because I don’t like them—places like Elsewhere Editions and Transit Children’s Editions are producing gorgeous objects that introduce kids to the world—but because I don’t come across them in everyday life (no one sends kids’ books for review), so I rely heavily on Publishers Weekly reviews to find the bulk of these. Which makes me feel like the data must be incomplete . . .

Regardless, if you’re looking for a holiday gift for a young’un, this book does sound powerful, and Martin Aitken is an award-winning, incredibly prolific translator, which is enough to persuade me that this must be good.

A sensitive portrayal of loss, My Brother is the story of a child whose brother emerges from the depths of the fjord on the end of her father’s fishing line. Though grieving in different ways, the child and her father find comfort in remembering their brother and son together. Øyvind Torseter’s wobbly line drawings and dark cross-hatched blotches sprawl across pages bathed in warm reds and oranges, melancholy blues, and hopeful greens. Accompanied by Torseter’s captivating images, Laura Djupvik’s poetic lines provide an opening for children and adults to talk about grief and the power of memory.

2019

As alluded to above, since I started putting this database together, I’ve used Publishers Weekly as a primary source for finding translations. I’m currently up to the June 5, 2023 issue, and once I get totally caught up, those charts above will look pretty different.

But it would be foolish to believe that PW reviews every translation that comes out in a given year. Even if there’s a reasonable number of translations in a given year, like the 720+ that came out in 2016, that’s still seven hundred and twenty books to review, or approximately 14 per issue. There’s no way PW has the capacity to review all of these titles. Not to mention the huge chunk they never even know about, since not every press has their shit together enough to submit all their books to PW for potential review.

So, to supplement what I pull from PW, I try and go through every press’s catalog (as listed on iPage) once a year, focusing on the presses that have traditionally published the most translations, but digging into the backlist whenever a “new” press comes to my attention. (Before updating the Google Spreadsheet, I entered all the Sandorf Passage books, since they’re relatively young and a good number of their books came out during the data entry drought of 2023 till now.)

Although publishing translations shouldn’t be a volume game—printing is not publishing—it is undeniably interesting to run the list of which publishers published the most translations in a given year. Which, for years now, has meant AmazonCrossing, Europa, Seagull, and New Directions.

To put this in context, AmazonCrossing is at the top (currently) with 466, and New Directions—a favorite press among most every literary reader, and which is fifth in overall translation production—has 234 original works in the Translation Database, including:

EEG by Daša Drndić, translated from the Croatian by Celia Hawkesworth

This novel has the dubious honor of winning the final (at least for now) Best Translated Book Award for Fiction. When the BTBAs launched in 2008, the National Book Award from ALTA and the PEN Translation Prizes were the only other major awards for literature in translation independent of source language, and the prize—modeled on the National Book Critics Circle model—filled a particular hole in book culture. Whereas the NTA is primarily judged by translators, who, at least in an early round, compare the original text against the translation, the BTBA juries—which consisted of critics and booksellers in addition to translators—focused more on the book as it appeared in English. Given that leaning, along with the makeup of the jury itself, the BTBAs tended to elevate more strange and edgy works than most other book awards, with authors like recent Nobel Prize-winner László Krasznahorkai taking home the honors twice in a row with two different translators (George Szirtes and Satantango in 2013; Ottilie Mulzet and Seiobo There Below in 2014), Can Xue & Annelise Finegan Wasmoen for The Last Lover in 2015, Wiesław Myśliwski & Bill Johnston for Stone Upon Stone in 2011, and Attila Bartis & Imre Goldstein for Tranquility in 2009.

Our final award ceremony (hopefully not last) took place on May 11, 2020, over Zoom. The link got porn bombed at one point (remember when that was a thing?), but it was a wonderful, warm experience during that very weird time.

I do dream of bringing this back, but with a specific focus or set of judges that would differentiate it from the National Book Award for Translated Literature (which launched in 2018) and the NBCC Greg Barrios Book in Translation Prize (launched in 2022). The Cercador Prize (launched in 2023, and which just announced The Queen of Swords by Jazmina Barrera & Christina MacSweeney as its 2025 winner) is similar in spirit, but yet different. All of this would be possible if the BTBA had a new sponsor . . .

2008

Which brings me back to the beginning. And the possibly half-invented story of how the Translation Database came to be.

In 2007, Iowa’s International Writing Program turned 40, and to celebrate, they hosted a series of panels about international literature. I don’t remember any specific topics, but I do remember two things that took place: 1) I met Margaret Schwartz, who happened to be working on Macedonio Fernández, which lead to the publication of The Museum of Eterna’s Novel (The First Good Novel), and 2) Eliot Weinberger told me that I should’ve named our website “point three percent,” because there was no way that three percent of all the books published in America were works in translation.

I believe part of his argument was based on being a judge for the PEN Translation Prize and the assumption that most every book in translation that came out that given year would’ve been sent to the judges. And that he only received a couple hundred—not thousands.

Which is a great point. The 3% figure—which we made famous, for better or for worse—came from a couple different sources: an informal NEA study of the percentage of translations reviewed in trade journals, and Bowker’s attempt to mine their own data for the relaunch of the PEN World Voices Festival. Both studies were incredibly valuable in bringing attention to the state of literature in translation in America, in part because they both arrived at the same general conclusion: approximately 3% of all books being published here were originally written in a language other than English.

What neither study had though, were specifics.2 But if Eliot was right, and there were only a few hundred translations every year, then couldn’t we count them all?

So I came back from my first ever trip to Iowa with a plan. I did have to set myself some parameters to avoid going insane—books published in English for the first time ever, eliminating new translations of classics along with reprints and reissues, and fiction and poetry only—but I got a copy of the Translation Review with a list of books received, and started visiting publisher website after publisher website, gathering catalogs at BookExpo America, and emailing book offices, consulates, ALTA to try and capture at least 2008 in full.

At this moment, I’ve identified 390 translations published in 2008, but the infomation on nonfiction or children’s titles is incomplete, so this will definitely grow over the next few months. (A database is a living thing.) But as a way of closing out this quick overview, here’s what I believe was the very first book ever entered into the database:

Between Two Seas by Carmine Abate, translated from the Italian by Antony Shugaar (Europa Editions)

The book is now out of print, but here’s what Publishers Weekly had to say about it:

Steeped in the muggy summers and rich culture of Calabria, Abate’s American debut is the intoxicating story of a man’s lifelong obsession to raise from long-abandoned ruins a legendary family inn once visited by Alexandre Dumas. Giorgio Bellusci, born in 1927, is by middle age a relatively prosperous butcher and landowner who answer the demands of local gangsters for protection money with an outburst of murderous violence that sends him to prison. But his dream doesn’t die, and he begins work on the inn after being released. The gangsters, meanwhile, want their revenge and blow up the almost reconstructed Fondaco del Fico. With some creative fund-raising and the assistance of Florian, the novel’s narrator, the now elderly Giorgio succeeds in finishing his life’s work. Abate populates this magical novel with a cast of captivating, emotionally complex characters drawn from multiple generations and from across time, and recreates the rhythms of life in a small village with poetic affection.

Next month I’ll be back with another general update and a look at the eight titles I’m planning on using in my spring class on international literature. Picking these out is always a joy; writing about them is even better.

In the meantime, if you’d like to help fill out this database please fill out this form, or email me information about your book, or send a review copy to our office. I thank you in advance, and I hope you enjoy playing with the Translation Database as much as I do!

This database still functions, but since it’s so much quicker for me to add titles into FileMaker and then export them, I’m trying to catch up here first. Stay tuned for either an update to the PW data or information about a new way to search the database in real time. Till then, this is the complete contents of the database as of today.

Nor did they really have a well-defined denominator. Counting the total number of books is slippery—should one include self-published or not? are we talking all books or just works of fiction? what do foreign language textbooks show up as? is manga included?—and depending on how many titles a year we use as the base, it’s almost impossible to imagine the number of translations increasing enough to significantly alter that 3% figure. Especially if you assume the total number of published books increases year over year. If there are 230,000 titles one year, and then 240,000 the next, you would have to go from 6,900 translations to 12,000 to move the needle from 3% to 5%. Which is why I’ve been trying for years to move off the idea of the percentage as a benchmark, and instead focus on the actual, individual books that are being published.