Janet Heidinger Kafka Prize Finalists 2025

Here are the list of finalists for the University of Rochester's award for promising, up-and-coming women writers.

We’re extremely honored to be announcing this year’s finalists—and eventually, the winner—of the 2025 Janet Heidinger Kafka Prize, a quite prestigious annual prize ($15K to the winner!) awarded through the University of Rochester to a work of prose written by a woman early in their career.

The full list of past winners is pretty amazing, and includes: Kathryn Davis, Ru Freeman, Mary Gordon, Ursula LeGuin, Toni Morrison, Ann Patchett, Jessamyn West, and Karen Tei Yamashita, among many other writers who have gone on to have illustrious careers.

This is my fourth time serving on the jury, which has been an incredible experience, providing me with the chance to read a ton of contemporary works written by American women writers and get a sense of various trends, styles, interests, etc. Along with four other judges,1 we evaluate around 200 titles published the previous year (all novels and short story collections) and narrow it down to a final ten . . . Or, in the case of this year, eleven, because I’m incapable of following directions. (Shocking.)

Before getting to the list of finalists, here’s a bit of background about the prize:

Since 1976, the Susan B. Anthony Institute for Gender, Sexuality, and Women's Studies and the Department of English at the University of Rochester have awarded the Janet Heidinger Kafka Prize for fiction by an American woman.

This prize was created in honor and memory of Janet Heidinger Kafka, a young editor who was killed in a car accident just as her career was beginning. Those who knew her believed she would do much to further the causes of literature and women. Her family, friends, and professional associates created the endowment from which the prize is bestowed, in memory of Janet Heidinger Kafka and the literary standards and personal ideals for which she stood.

Each year a substantial cash prize is awarded annually to a woman who is a US citizen, and who has written the best book-length work of prose fiction, whether novel, short stories, or experimental writing. We are interested in calling attention to the work of a promising but less established writer.

If you’re a publisher who would like to submit a work for the 2026 award, first read the criteria found here, and then simply fill out this form. (And please, self-published titles are not eligible, and if the author has already published 3+ books and/or won a major award, they’re unlikely to win this prize. Thanks!)

All eleven finalists are listed below in alpha order by last name, with a brief quote about each. Personally, I’ve read five so far, and am looking forward to the other half-dozen and, especially, talking all these over with the other judges . . .

Smothermoss by Alisa Alering (Tin House Books)

In their deliciously weird debut novel, Smothermoss, Alisa Alering flashes us to rural 1980s Appalachia, where two young sisters at odds with each other—and themselves—are drawn into a murder that turns very strange indeed.

Growing up in a ramshackle house on a mountain, 17-year-old Sheila dreams of escape, or at least a life where their family doesn’t have to forage for mushrooms and dandelions or raise rabbits for the pot. The fantasy seems impossible, especially if “your dad is dead and your brother is in prison and your mom comes home from the Iron Mountain asylum at 8 in the morning in a wrinkled uniform with dark circles under her eyes.”

She has a 12-year-old half sister, Angie, but they’re so different “they don’t even seem to be the same species.” Angie doesn’t care that the kids she goes to school with have decided she’s dirty and smelly, a liar and a thief. She’s preoccupied with drawing grotesquely beautiful monster cards she believes can divine the future, like her own D.I.Y. tarot deck, and pretending to be an action hero fighting imaginary bad guys in the woods.

Until, that is, a real bad guy arrives.

Mercury by Amy Jo Burns (Celadon Books)

In 1990, just a few weeks before the elder two Joseph sons are to begin their senior year of high school, the beautiful Marley and her mother blow “into Mercury in their teal Acura with the windows down and the radio blasting.” Not long after they arrive, two outfielders catch Marley’s eye at a baseball game: Baylor and Waylon Joseph, who have “V-shaped torsos and dark hair.” One taunts the other, they get into a brawl and Marley clambers “down the bleachers to climb the fence and force the brothers apart.”

With this single act, her fate is set. She becomes lover, mother, arbitrator, therapist and boss—every possible thing to the two boys and their younger brother, Shay. [. . .]

Though the book covers only nine years, there’s something epic about the love story at its heart. And it is a love story, even if there’s little romance involved. The Josephs, Marley, maybe all the people of Mercury—none are terribly articulate about how they feel and what they want, so they express themselves by fighting, drinking and disappearing. We know early on that Marley marries Waylon Joseph while still in high school, but which brother Marley truly loves is one of many driving forces in this novel—a stronger one than the body in the attic. Another is the question of who deserves Marley’s loyalty.

Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato (Grove Press, Black Cat)

In Bruna Dantas Lobato’s debut novel, Blue Light Hours, a young woman from the Brazilian city of Natal enrolls at a college in Vermont. The school has offered her a full-ride scholarship, and she works in the campus mail room. As the story begins, her friend Najwa, a student from Palestine, tells her that “I thought traveling would be easier once I was at a fancy international school in Europe, that I’d feel like the world was small, that I could just hop on a flight and be back home. But in the four years I spent in the Netherlands, I didn’t go back to Palestine once.” But her friend Safia responds that when she was at a boarding school in Pakistan and went home to visit, parting from her roommates always made her cry. Our unnamed narrator says, “I stared into my green tea, wishing someone like Najwa had warned me about how hard it would be to leave, how hard to stay.” [. . .]

Blue Light Hours has a placid surface, not quite toneless but reserved, reflective. The troubles that arise may disturb the speaker’s composure, but their persistence provides a basis for assessment and wondering. Although the novel certainly fits into the category of immigration tales, it isn’t preoccupied with alienation or discrimination. It is, rather, a novel essentially about decision-making and the uncertainties involved in experiencing a crucial change. In one sense, the reader is in the same position as the mother – one hears the spare prose, the quiet clarity of the student’s urgencies, and asks for more even if the “news” is modest. On the other hand, only the reader is privileged to hear the continuity of her thoughts, and to envision scenes such as a dorm party.

Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Scaffolding has a double narrative: two young couples living in the same apartment in north-east Paris in 1972 and 2019. Both women are psychologists contemplating motherhood: Anna in 2019 is a psychoanalyst on leave after a late miscarriage; while Florence in 1972 is hoping to conceive with her husband, Henry, who doesn’t much want a baby and isn’t consistently sure he wants a wife. French-American Anna introduces us to “the Parisian apartment I had always dreamed of living in,” imagined since childhood Christmas trips to Paris with her French mother. It has “all the indispensable Haussmannian details” and is “high enough on the hill to see all the nearby rooftops and beyond.” It would have been the scene of a sociable family life, “but then the baby didn’t come.”

Scaffolding is absolutely a novel of ideas. Not much happens and plot development is mostly psychological, interior in both spatial and intellectual ways. The prose is as well crafted as Elkin’s nonfiction leads us to expect, and the characters are very finely developed. She writes beautifully about ennui, literal and metaphorical disorientation, and the love of place. Not every good essayist should write a novel, but we should be glad Lauren Elkin did.

Mouth: Stories by Puloma Ghosh (Astra House)

“I thought we were happy, until the wolves came.” This line from one of the stories in Puloma Ghosh’s debut collection reads almost as a logline for the rest. These unsettling fictions are often set after minor apocalypses, the protagonists standing in the aftermath and facing the mismatch of who they once were and who they are now. In this way, Mouth is a welcome book for our post-COVID era, though what gives the collection its power is the dissemblance of Ghosh’s worlds to our own.

These are stories concerned not so much with recovery after loss as with preservation, how the woman at each story’s center can stay whole when so much of her has been stripped away. This drive for wholeness gives Ghosh her collection’s title and central metaphor: the mouth as an organ for consumption. Pritha, an ice-skating rival of the protagonist in “Desiccation,” is discovered “crouched against [a] gray wall, her teeth deep in a crumpled rodent”; later, she sucks lightly on the protagonist’s wounds. In “Supergiant,” an international pop star sits calmly as her makeup artist digs deep into her mouth, unhooking the seams of the “celebrity skin” that forms her public self. Many of Ghosh’s characters at one point get their necks and shoulders bitten, some of them benignly, but one to the extent that she’s left bleeding everywhere, “and I leaned into it, longing to let all of my writhing insides spill forth at last.”

Fruit of the Dead by Rachel Lyon (Scribner)

Quick: What do Edith Wharton, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Geoffrey Chaucer and the Australian experimental rock duo Dead Can Dance have in common? Answer: All have been inspired by the tale of Persephone, Demeter and Hades. The art resulting from this inspiration has ranged from prose to poetry to haunting darkwave jams.

Joining these luminaries (and still others, Ezra Pound and Dante Gabriel Rossetti among them) is Rachel Lyon, whose second novel, Fruit of the Dead, turns Persephone into a pink-haired slacker and Hades into a hybrid of Jeffrey Epstein and Richard Sackler. [. . .]

In Lyon’s capable update, Persephone becomes Cory Ansel, a recent high school graduate who has been accepted to zero colleges and is working as a camp counselor to kill time until her next move. Demeter—the goddess of grain—becomes Emer Ansel, an executive at an agricultural NGO. Hades is Rolo Picazo, the billionaire C.E.O. of a pharmaceutical company that manufactures a drug similar to OxyContin.

On the last night of camp, Cory smokes weed with her fellow counselors and experiences wonderment about the human brain—a “corrugated ball of tender muck, synapses snapping like microscopic firecrackers,” in one of Lyon’s more bedazzled sentences. The philosophizing is interrupted when Rolo, who has come to fetch his son, invites Cory to dinner.

In a span of minutes the older man displays a United Nations’ worth of flags, all of them red. First he asks Cory if she’s a model. Then he insists on hand-feeding her a forkful of bacon. Finally he offers her a lucrative and ill-defined job contingent upon the immediate signing of an NDA. Run, Cory, run!

The Fetishist by Katherine Min (Putnam)

“It's going to have many characters, omniscient narration. Lots . . . is going to happen—suicide, kidnapping, attempted murder. It'll be arch and clever but also heartfelt; I'm gonna channel Nabokov.”

Exactly! At the center of The Fetishist are a cellist named Alma Soon Ja Lee and a violinist named Daniel Karmody; the two had a passionate affair twenty years before the novel begins. It was broken off due to an infidelity that ultimately caused the aforementioned suicide, kidnapping and attempted murder. Min brings in another pair of lovers: tiny, miserable, 23-year-old Kyoko and her 6’3”, 295-pound Black boyfriend and bandmate, Kornell.

In the novel’s present, Alma has been forced into retirement by a diagnosis of MS and, early on, has a seizure that leaves her in a coma. While unconscious, she reflects on her romantic history, as revealed in a chapter titled “Alma and the March of the Rice Kings.” [. . .]

There's hardly a sentence in this book—feverish and funny and razor-sharp—that does not merit quoting.

Poor Deer by Claire Oshetsky (Ecco)

Midway through Claire Oshetsky’s beautiful, terrifying sophomore novel, a mother asks her daughter: “Did you leave Agnes Bickford in that cooler to die, Bunny?”

This turns out to be the central question of Poor Deer.

Bunny is Margaret Murphy, our protagonist; Agnes Bickford is her childhood best friend and neighbor. On a rainy day when the girls were 4 years old, they raced out of their respective houses to play. Later, Margaret’s mother found her daughter silently cowering under her dining room table. Agnes’s mother found her daughter dead in a tool shed.

What happened, who’s at fault, and is this person deserving of forgiveness? These uncertainties haunt just about everybody in the novel, especially Margaret herself. [. . .]

Grief is a well-trod territory in fiction, but in Oshetsky’s hands, this familiar topic becomes fresh and strange. The book’s narrative structure mirrors the grief-stricken mind—starting, stopping, looping back, stuttering, marching grimly forward. With her voice “like the drilling of a tooth” and eyes that “flash in primary colors,” Poor Deer is a frightening anthropomorphism of the cruel inner monologue that so many of us hear in our lowest moments.

Honeymoons in Temporary Locations by Ashley Shelby (University of Minnesota Press)

The threat of climate change looms over the short stories of Ashley Shelby’s Honeymoons in Temporary Locations, resulting in a zesty mix of humor, speculative science fiction, and melancholia.

Set in a future wracked by environmental decay, “Muri” is a far-out ecofable in which polar bears being relocated to the South Pole rebel against the human crew of their transport vessel; visceral violence gives way to tragedy. And “Honeymoons in Temporary Locations” is intricate, set in a climate-compromised future wherein the rich relocate to inland safe zones while the poor fend for themselves. Its grim commentary on inequality and bureaucracy is elevated by an ever-shifting romance between two women whose erratic relationship mirrors the changes affecting the world. [. . .]

Tongue-in-cheek, mournful, and inventive, Honeymoons in Temporary Locations is a bracing collection of cautionary tales regarding the too-probable near future.

The Sisters K by Maureen Sun (Unnamed Press)

As the title suggests, the novel draws inspiration and influence from The Brothers Karamazov—it is about a fraught inheritance—but it doesn’t set out to re-do the book. Sun’s dying patriarch is Eugene Kim, a cheese-ball real estate mogul and comically awful person who, though on his death bed, verbally and physically abuses anyone near him, forcing his three daughters and one illegitimate son to endure his malevolent caprices and volcanic insults as they clean out over-flowing mugs of sputum and deal with his literal shit. Two of the girls, Sarah and Minah, openly despise him; the son (Edwin) seeks his money with calm, shark-like focus; the youngest girl (Esther) is the only one who feels real compassion for him—a compassion that is almost impersonal in its constancy, and which is perhaps as much about the maintenance of Esther’s own dignity as anything. She and Edwin are the only ones who make themselves fully available to physically care for Eugene (there is a parade of victimized or buffoonishly scheming home-aides), as he rants that the truly gentle Esther is “a dirty whore” and gloats, albeit affectionately, as exhausted Edwin scrubs his toilet. [. . .]

It sounds dark because it is. All the characters are in varied states of anguish; everyone except Esther is hypervigilant, calculating, furious and desperate. The sisters are deeply attached to each other, even as they are suspicious of the feeling; they experience their attachment most intensely through shared pain. [. . .]

I can have a reflexive dislike for novels of ideas, and I realize that this sounds like exactly that. But it doesn’t read like that. It doesn’t read like that because of Sun’s attention to the material and visceral elements of each character, her rare tactile apprehension of emotional life and how that interacts with thoughts/ideas. And then there is her attunement to what might be called natural goodness. Terrible things are narrated in the story, events from which the sisters may not recover; there is bitterness and regret. And yet goodness abides, in the character of Esther and also in her sisters’ receptivity to her

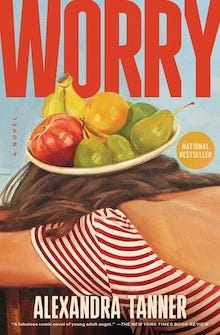

Worry by Alexandra Tanner (Scribner)

Jules is a 28-year-old aspiring writer from Florida with an M.F.A. in fiction and a day job at a website that sells study guides of classic novels. In claustrophobic present tense she candidly narrates the minutiae of her fixations, disappointments, aversions and maladjustments as she navigates adulthood.

At the risk of being too schematic, Jules’s interests, beyond her efforts to achieve literary renown, can be boiled down to consuming “Christian Mommy” social media content and critiquing her sister, Poppy. The former is symptomatic of a larger personal complex—though Jules wants to be independent, she craves a matriarchal authority’s approval, guidance and comfort, perhaps because her own mother can be rejecting and inscrutable. In its more superficial manifestation, Jules’s curiosity consists of scrolling the internet for hours each day, watching Instagram moms share conspiracy theories in all-caps and hawk products. [. . .]

Tanner works wonders with little character development (I’d call it “character entrenchment”) and hardly any plot (eventually, Jules and Poppy go to Florida for Thanksgiving), trusting humor to structure the story all the way through. The novel runs on an engine that relentlessly converts suffering, usually of the inner-turmoil variety, into comedic relief.

Speaking from experience, Worry also nails what it was like to be a youngish media worker in Brooklyn in 2019—desperate for meaningful success in a crumbling industry, addicted to the fleeting dopamine hits of social media, online shopping and clicking “send” on grant applications. It’s funnier than it should be.

Stay tuned to find out which of these eleven titles will win this year’s prize, and for details about the reading and celebration that will take place at the University of Rochester and online this fall.

In the meantime, hopefully one or more of these caught your interest!

This year’s set of judges includes: Eileen Daly-Boas (chair), Rachel O’Donnell, Laura Whitebell, and Taylor Thomas. All reside in Rochester, with Taylor owning one of the premiere local bookstores, Archivist Books.